Carrie A.

Based in: Bay Area, California

Hometown: Bay Area, California

Industry: “Creative.” Writer currently working in DEI, Marketing & Education

Age: 33

Instagram: @carrieelysia

Carrie A. is the daughter of Louisiana Creoles, raised on James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, red beans & rice and miles of golden Pacific coastline. She is a womanist, a writer, a wife and mother of four, currently working at the intersection of marketing, DEI and education.

How conscious are you of your race and that of your children?

As a Black American woman & mother, race is a continuous undercurrent in my life. It is with me at the grocery store and in the doctor’s office, at my children’s schools, my job and at the dinner table, where my family delves into the news of the day. Undoubtedly, race has a great deal to do with how I am outwardly perceived — a constant with which every Black person alive has had to reckon, at some point or another.

In my inner world, I have a more intimate relationship with my racial identity. I was adopted from birth by my Black parents, who raised me in California with deep ties to their home in New Orleans, Louisiana. My biological father is Black, from Southern California. My biological mother is white, originally from Australia. She turned 18 two weeks before I was born, and it is with great love and what I suspect was a grace and wisdom beyond her years that she elected to find two loving Black parents to raise me. It is my understanding that she felt, if she could not raise me herself, that I would be most deeply cared for in a Black family. This act is the most selfless gift anyone has ever given me.

I can say without hesitation that Blackness is the most vibrant strand in the great tapestry of my life. I embrace the remarkable history I carry in my features, in my blood and in my language; most notably, in my love of the spoken and written word, as it has been passed down to us through generations of storytelling, song and rhythm.

I remember the first time I read Zora Neale Hurston’s controversial piece, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me” in which she addresses the idea of race with a freedom I’d never seen on the page before. From the inheritance of a depth (represented by jazz) that white people can never quite access, to the transience, and ultimately, limitations of the words used to categorize Black people. She writes,

““I am not tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes... No, I do not weep at the world—I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife.” Then later, “At certain times I have no race, I am me. When I set my hat at a certain angle and saunter down Seventh Avenue... The cosmic Zora emerges. I belong to no race nor time... I am the eternal feminine with its string of beads...Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.””

While I may not always be as resolute as Hurston, her words remain in my spirit, especially as I’ve evolved into a mother. I have four children with my white, Jewish husband: two bi-racial Black stepchildren (14 and 13 years old) and two bi-racial Black toddlers (4 and 2 years old) whom I brought, vividly screaming, into existence.

In a world that threatens the humanity of Black people, I want my children to be prepared, but I also want them to grow up knowing their inextricable value. I want them to know their history, through their own exploration of Black, Indigineous, POC & Queer voices. I want them to love themselves fully and with the kind of freedom that Hurston’s words inspire.

They are so young now, but they feel everything. Daily, I am in awe of our two oldest — at their political and social consciousness and their will to honor their Black heritage, even, and perhaps especially, when they are the only Black kids in the room, as I so often was at their age.

Do you recall the first time you faced some sort of microaggression or blatant discrimination? Walk us through that.

It’s hard to recall the very first instance of discrimination I experienced, mostly, because my young, young life is filled with memories of my mother being followed and stopped in department stores, even when she dressed impeccably; even when she said all the right things. Or watching from my car seat, as blue and red lights ushered us to the side of the road whenever we were driving through a “nice” neighborhood in our “nice” car. Or when my elementary school friend invited me over to her sprawling estate, where I’d spent many playdates swimming in her pool or jumping on her trampoline; only to call back minutes later to inform me I couldn’t come because her grandma was visiting and was worried I might hurt her.

I didn’t know nuanced terms like “respectability politics” as a little person, but I was conscious enough to understand (because my parents made sure of it) that having parents with advanced degrees and a house in a wealthy zip code does not protect anyone from racism. Those things may provide a level of economic security, but I grew up knowing that we were all navigating a system that was designed to exclude Black people, at its best, and at its very worst, to harm us.

I think the most visceral memories of discrimination I have as a kid are born from being the only Black student in my class, and one of just a handful at my Catholic elementary school. On the day of my First Communion in second grade, I remember excitedly pulling out my white dress, beaded with pearls around the collar and the shiny patent leather mary janes my mother and I picked out. She styled my mane of ringlets just so, with some hanging down in the front and the rest pulled back into an intricate bun, then laid a flower crown on top of my head, with delicate little ribbons that hung down the back. My family had flown in from New Orleans for the occasion and I felt so proud, getting ready to enter the church with all their glimmering eyes looking on. As my classmates processed down the aisle, a group of rowdy junior high boys stood on either side holding archways of flowers for us to pass through. I noticed them jeering and chanting something at me and as I got closer, I could make out, with pinprick accuracy, “She ain’t nothing but a hoochie mama. Hood rat. Hood rat. Hoochie mama.” I was seven years old and felt utterly humiliated and helpless, without entirely understanding why.

After the ceremony, everyone spilled out of the church into the rose garden to gather for pictures and refreshments. My family was larger, louder and Blacker than any of the other families present. And just as the polite chatter over tea sandwiches began, my tall, round-bellied uncle pulled a large iron cow bell out of a little white cotton liquor bag that he had tucked away in my aunt’s purse. That cow bell had been passed down through the generations, welded by hand a century (or more) prior. According to my uncle, it adorned the first cow his family raised on the farmland they owned just outside of New Orleans. One could deduce that the previous owners of that land were slaveholders. The first cow on the first land a Black family ever owned must’ve been the realization of a dream. And that cow bell was our talisman - a piece of family lore. Every time a member of our family reached a milestone worthy of recognition, you better believe my uncle was there, cow bell in hand. So naturally, on my special day, my uncle held it high above the crowd and rang it. The clamor of the bell was so loud, it reverberated in my chest; many in the crowd jerked their heads around in bewilderment and anger. I distinctly remember a feeling of clarity. When I walked into the church with my classmates that morning, my Blackness evoked ridicule, and worse, the kind of deep-seated ignorance that hypersexulizes Black women and girls — a seven year old with a flower crown. But when I walked out of the church and into the arms of my family, my Blackness evoked pride; the echo of my ancestors, alive in me.

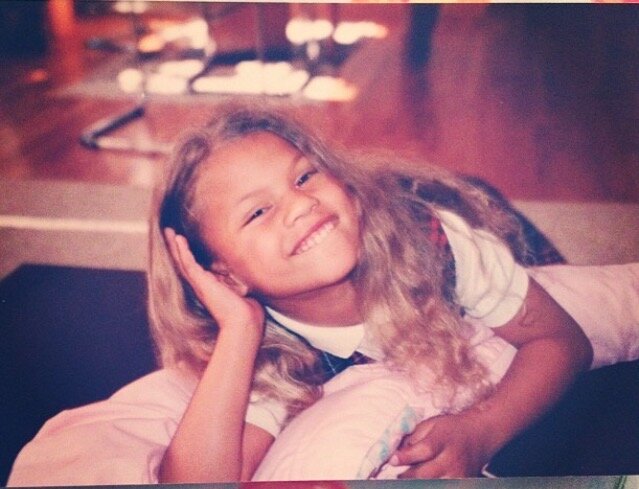

Kindergarten 1994

Are your children aware of their race? If so, how did you go about that conversation and at what age?

Our two teens are very aware of their race. We talk about the ways race plays out in their daily lives on a regular basis and have done since they were small. They are both vocal, seeking ways to uplift Black voices in school and in their social lives. They are coming of age in a political climate that weaponizes race and I’ve watched as they hone their ability to analyze the complexities — carving out their own perspectives and testing the waters in difficult discussions with friends, many of whom may be confronting these issues for the first time. My stepdaughter wrote in a recent school project, “The Black Lives Matter movement is not a trend,” in response, I’m sure to the rise in what I and so many others recognize as age-old performative allyship.

Race is the water within which we swim. So I guess I should not have been surprised when my four year old son declared, “We are a Black family with a white family inside because Dad is a white.” Or when he pointed out how light his little sister’s skin is compared to his own. But my heart still aches a little. As much as I want to encourage his curiosity and self-discovery, I am sensitive to these early perceptions of race. There is a world outside of our doorstep that will project messages about race that I am not comfortable with - particularly in the comparison of my curly haired, brown child and my blonde, white-passing child. I had to catch myself, very early on, in the language I used to describe my daughter’s physical appearance after she was born. I found myself trying to use humor to mask my insecurity about her white complexion and blue eyes — rooted in a deep fear that people will not recognize me as her mother. I have since realized that fear is my problem to sift through and will never be hers.

What has your race taught you?

Blackness is a deep well; we are survivors of a complex diasporic legacy. Because so many of us were robbed of knowing exactly where we come from, we carry our inheritance in our bones and in the way we speak; in our stories and in the dreams that we bring to life, often with little to no external support, often out of thin air. As Toni Morrison once noted, there is “”a rootedness — a knowing so deep,” embedded in us. And every descendant comes to it differently, yet we can all draw strength, strategy and humor from our shared experiences. I don’t quite know how to put this kind of love into words without romanticizing or trivializing it. But I love us. There is so much joy and beauty; there is so much depth and talent; there is so much pain and grief — all of it unique to Blackness, all of it ours.

“I don’t quite know how to put this kind of love into words without romanticizing or trivializing it. But I love us. There is so much joy and beauty; there is so much depth and talent; there is so much pain and grief — all of it unique to Blackness, all of it ours.”

How do you feel about the current social unrest, fight for Black people and Black lives and the sharp increase in hate crimes against Asians?

The fight for the inherent human dignity of Black people is not new. Nevertheless, it remains overdue. The swell in media coverage and boots on the ground in cities across the world has been inspiring but it is not enough.

I remember when the levees broke in New Orleans in 2005. Black people were stranded on rooftops, packed into overcrowded, ill-equipped “emergency centers” and dying on highway overpasses from the heat; from the lack of clean water and food. Katrina did not come close to ravaging New Orleans the way the failure of the federal government did. So many lives lost and destroyed in a major American city, all because they were Black and poor. My entire family relocated then rebuilt. Months later, they were still pulling Black bodies out of dilapidated houses; seeking the basics of electricity, clean water and food — a parallel to Texas 2021.

The climate crisis and racial unrest in this country will continue to collide until we decide to dismantle white supremacy — full stop. Black, brown and poor communities are the first to suffer, every time. During the uprisings in response to police brutality last summer, Cornell West stated in an interview, “We are witnessing America as a failed social experiment...the history of Black people in America for over 200+ years, is looking at America’s failure. It’s capitalist economy could not generate and deliver in such a way that people could live lives of decency.” The system was built on our backs and continues to profit by dehumanizing people of color.

Our Asian brothers and sisters are no exception. The dangerous anti-Asian rhetoric espoused by America’s leadership in response to the pandemic exposed new fears and played into old dehumanizing stereotypes that only serve to divide us.

How did your race affect your upbringing?

In a sense, I was raised in two worlds, simultaneously: I physically grew up in the rolling foothills of the tech capital of the world, just south of San Francisco but at my dinner table, I was brought up on the experiences, colloquialisms and wisdom of two Black Southerners, which was reflected in everything from the food we ate to the traditions we honored and the way we showed up for one another. My parents raised me to embrace Black culture, and I remain very proud of that heritage. My connection to my family in New Orleans was fortifying, in that sense. Even as an adopted child, I never questioned where I “fit in.” I looked like them. I talked like them. When visiting New Orleans, my aunts, uncles, cousins and particularly my grandmother, welcomed me home, uplifted me and made me feel whole.

How do you think your children's race will affect their upbringing?

I think about how my children’s race will affect their upbringing everyday. I hope they see it as a rich and inextricable part of themselves. I also, perhaps naively, hope they inherit more of the joy and so much less of “the fight.”

For example, Black mothers are constantly tasked with navigating biased social, medical and educational settings on behalf of our children. We are often dismissed and flagged as “angry” or “aggressive” for advocating for our children when our only aim is to give them a level playing field. Often, we have to create these opportunities ourselves, by whatever means that we can.

When the teens were young, we searched for representation in books and media so they grew up seeing themselves and their experiences reflected back to them. As they grew, some of the hard realities of bias and microaggressions set in. We guided them through, always wondering when we needed to let them sort it out themselves or when we needed to step into the ring. Today, they are equipped to engage in thought-provoking dialogue about race and also to bask in the Black humor and style that is steadily defining their generation.

I will continue to be their champion, in every way I know how, and like so many mothers before me, I’ll hold out hope that they get a little more time to be young and free, a little more shine in this life, and that they will land somewhere that values them as much as we do.

Is there a specific part of your culture that you feel is important for your children to embrace?

I want my children to revere Black storytelling, rhythm and music — to know how to sway on the front porch, hand in hand with their grandmother or grandfather and hear the whole world pass through their lips. I want them to understand everything it took for our Black elders to be here with us. I want my children to know the magic of witnessing, first-hand, the vibrant plumes of a Mardi Gras Indian’s costume on Mardi Gras day — of hearing them chant, “Won’t bow down, don’t know how” as a rally cry for Black resistance and self-expression. I want my children to know that no man-made border can contain them — that there are pieces of us across every ocean and glimmering monuments that we built with our own two hands.

When did you first realize you were “other”? Walk us through that experience.

White people used to stop my mother in the street to ask about my sandy-colored hair. To this day, it makes me cringe to remember how strangers dared to approach a Black woman and her young child with bold assertions about lineage and sometimes even rogue attempts to touch a curl. Rest assured, my mother never let anyone touch one single strand but, the audacity! On outings, I began to anticipate the attention and get nervous but my mother was always two steps ahead with a sharp quip to shut it all down. I learned that my racial identity would be called into question often and followed my mother’s lead with the firm knowledge that it was no one’s story to tell but mine.

What’s one way you think your life would have been different had you been born a different race?

My white, Jewish in-laws moved their young family across continents throughout the late 1970’s & 80’s and the memories of their adventures abroad are sometimes beyond imagination. While they are not an example of a “conventional” white family, I always admired the great autonomy with which my mother and father in law raised their children, particularly their daughters, who could negotiate in the markets of Thailand, catch a commuter train in Sri Lanka or swim with sharks in Catalunya, and go alone, without a second thought. To move through the world with such freedom is a liberty many women of color rarely experience, especially as it pertains to travel. I am steadily trying to break free of the stigma associated with Black travel, joined by a generation of Black millenials and Gen Z’ers who don’t have to grip a green book to see the world.

What privileges do you NOT have that others do?

As a Black woman, my existence oscillates wildly between invisibility and unwanted attention. I have been hyper-sexualized since I was a child, from seemingly innocuous comments about my features or appearance to predatory and violent behavior. Police follow me home in my own neighborhood. Teachers and bosses have consistently underestimated me and made me prove myself, despite my intelligence and qualifications. In my everyday interactions with doctors, grocery clerks, salespeople at department stores and even sometimes parents at my children’s schools, I am often ignored or passed over unless I go out of my way to make myself or my needs known. White doctors and nurses let me labor through a respiratory episode, alone with my husband for two days, before delivering my first baby, during a time when the soaring Black maternal mortality rate was making national headlines; a world away from my experience with my Black midwife, who stayed in rhythm with me from start to finish during the delivery of my baby girl. I play out scenarios in my mind to gauge my safety before taking action and sometimes, fatigue over the anticipation of poor treatment or fear of danger prevent me from engaging altogether.

“As a Black woman, my existence oscillates wildly between invisibility and unwanted attention. I have been hyper-sexualized since I was a child, from seemingly innocuous comments about my features or appearance to predatory and violent behavior. Police follow me home in my own neighborhood. Teachers and bosses have consistently underestimated me and made me prove myself, despite my intelligence and qualifications. In my everyday interactions with doctors, grocery clerks, salespeople at department stores and even sometimes parents at my children’s schools, I am often ignored or passed over unless I go out of my way to make myself or my needs known. ”

What privileges do you HAVE that others don’t?

I am a light-skinned Black woman who attended private academic institutions and lived in affluent neighborhoods my whole life. As a creative person, I explored and experimented with different callings, all with the knowledge that there was a strong safety net to catch me if and when I fell. I have made room in my life for travel; to expose my children to other cultures and countries on long trips that have enriched my life. And while my husband is a smart, conscious, loving partner in this journey of raising bi-racial Black children, he is still a physically dominant white male, with all the privilege such an identity suggests. In fact, being married to a white man is sometimes a painful study in proximity to privilege. I’ve witnessed how I am treated differently, oftentimes better, when he is beside me.

What is one way you think you could connect specifically with people who have differing and/or negative views towards your race?

I was the only Black student sitting in a sociology class the night that a grand jury decided not to indict Michael Brown’s killer. My professor opened up the floor for discussion and I listened as one, by one, my white, Asian and Latinx classmates presented arguments for his murder, all of which fell into the same tired categories with which Black people are painfully familiar: he should’ve listened to police; there was evidence of drugs; he might have been violent given his “troubling” past. They held each accusation up with such conviction — with so little regard for the sanctity of this teenager’s life; the real flesh and blood human being who didn’t deserve to be gunned down in the street. I argued tirelessly on my own, for Brown’s right to live, and was met with resistance at every word. One woman argued that the tragic murder of her father at the hands of two Black gunmen, was why Michael Brown (an entirely different human being with no connection to the two men who shot her father) deserved to die. I knew then that the one-sided dialogue would never bear fruit and I waited until I got into my car to cry all the way home.

I’ve reflected on that night many times, wondering if there was anything I could’ve said differently to sway opinion — not because I was overly concerned with those particular people’s beliefs but because it was the first time I’d ever been physically present in a room full of people so candid about their own racial bias. I imagined this is what most of the country would sound like, if I were the proverbial fly on the wall.

My first takeaway is that racism is not my problem to solve. It is a psychological impairment that I do not possess and it’s therefore up to the impaired and the people who support them to treat, to heal, to eradicate. My second takeaway is that people who nurture these beliefs have never watched a system eat up their brothers and fathers. They’ve never eaten at my auntie’s kitchen table or traced their fingers along the lines of all the lives my grandmother lived, etched across her hands; they’ve never felt the kind of sisterhood that gathers up your whole being with one look or stayed up late while their mamas lovingly applied a salve to their scalps and braided their hair for the first day of school. They’ve never found their long lost ancestors in the beautiful ache of the blues or in the deep blue waters of the Atlantic. Because, baby! If they did! We’d live in a different kind of world.

In your opinion, how can we aim to raise children to be kind, compassionate beings, who care about equality for all?

I believe kids should be exposed to the experiences of people who do not look or think like them, early and often. Parents of all backgrounds (not just Black parents) should raise their kids to know how to talk about race and respect cultures that differ from their own. I’m all for instilling love and appreciation of heritage by teaching kids where they come from, but they must also be able to think about the person next to them, who may be different or vulnerable. I’ve found that exposure to travel and service are two immersive experiences that teach children about difference in a way that emphasizes human connection and kindness.

Is there anything else you want to say on this topic?

There is no Black monolith. There are deep ties that gather us. There is an undeniable search for freedom, for justice, for a place in the sun. There is a sacred unity in Black motherhood. From the outside looking in, what some mistake for “sameness” is the potency of our culture: the okra seeds we braided into our hair as we were shipped across the Atlantic — a taste of home to cling to (can you imagine the presence of mind?); the traditions, longings and strategies for survival we hid in our music; the language we preserved from bits and pieces of native lands we may never know or see again; the way we make do; the way we make life. We are not the same but we share, “a knowing so deep.”

Publish date: June 28, 2021